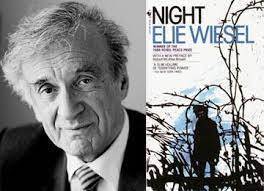

When Heaven Stays Silent: God in Elie Wiesel’s Night

The first time I read Night, by Elie Wiesel, I didn’t expect the weight of its silence and quiet. Not the quiet we enjoy, in peace or rest, but the kind that lingers in your lungs, the kind the you feel in your bones. While Elie Wiesel’s memoir focuses on his experience through the Holocaust, it also focuses on what happens when the God you were taught to love and trust stops answering.

In the early chapters, Eliezer is a young and devout child immersed in Jewish learning and prayer. He seeks God earnestly the same way a child would look for his father’s face in a crowd. But as he faces the horrors of Auschwitz, the God he knew in his childhood becomes harder and harder to find. Though his prayers remain, the presence behind them starts to dwindle and vanish.

“Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust.”

This loss of belief isn’t comparable to a form of atheism in its comfortable, philosophical form, but a cry of betrayal, exuding the agony of someone who believed, and now finds himself abandoned.

Silence as a Character

Wiesel’s genius lies in making God’s silence feel like an active presence in the book. It’s not just that God doesn’t intervene, but his absence is so heavy it further shapes the emotional climate of the camp. Silence almost becomes a character in this sense, cold, immovable, and unyielding.

In one of the memoir’s most haunting moments, as a young boy is hanged and dies slowly in front of the prisoners, someone behind Wiesel asks, “Where is God now?” And the voice inside him answers: “He is hanging here on this gallows.”

Here, silence is not just emptiness, it’s a brutal reframing of the divine. God is no longer enthroned in heaven, but brought down into the scene of suffering, bound and dying with His people. It’s a statement that is at once deeply theological and deeply blasphemous, depending on who reads it.

Theological Echoes

The silence of God is not unique to Wiesel’s memoir. The Psalms cry out: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22 NIV) , words later echoed by Jesus on the cross. Job sits in ashes, demanding an answer from a God who speaks only after long, aching chapters of waiting.

But in Night, there is no dramatic final speech from the whirlwind. No voice from the heavens to make sense of the pain, the silence remains unbroken. In this way, Wiesel’s text refuses the comfort that biblical narratives sometimes offer. It leaves the reader in the same unresolved tension as the survivor.

Faith After the Silence

Some readers interpret Night as a story of a lost faith, while others may see it as a story of a faith that has been burned down to its most fragile ember, just not yet extinguished. Wiesel himself said he never stopped believing in God, but he did lose the God he knew of his childhood. What remains is his faith stripped bare, existing in spite of God’s silence, not because of His voice.

Perhaps that’s what makes the memoir so enduring, as it doesn’t give a direct answer, but forces readers to sit with the question, becoming a mirror for our own seasons of divine quiet.

Why It Matters Now

In an age where quick answers and inspirational slogans dominate the conversation about faith and our society continues to be focused on the superficialities of the world, Night offers something rare, the unflinching portrait of belief that has been through fire, reminding us that silence is part of the story of faith, not an interruption to it. To be faithful is not just to hear God clearly, but to endure in the shadow of His absence.

Question for Readers:

Have you ever experienced a season where God felt silent? How did it change your understanding of faith?

Leave a comment